Insights

Michaela Bakala for E15: Every Change is Hope

December 16, 2024

Michaela Bakala is one of the few Czech women who have decided to support changes in society, devoting her name and all her time to this cause. In an extensive interview for e15 Magazine on the topic of philanthropy, she talks, among other things, about how Madeleine Albright encouraged her to apply her worldview in politics. "But I always tried to explain to her that I work where I feel I can make an impact," Michaela Bakala says.

Text: Petr Weikert

Photo: Tomáš Binter

What do you expect the students you send out into the world to bring back to the Czech Republic?

We now have approximately 220 young people who have studied or are currently studying at outstanding universities around the world, and most of them return to the Czech Republic. Some come back immediately after their studies, others after working briefly abroad, but they often return with a clear idea of where they want to make an impact.

I appreciate that they bring critical thinking and the ability to compare different approaches. Many of them strive to give back to society in areas like education, business, justice, or healthcare. For instance, Petr Winkler, a graduate of King’s College London, now leads the National Institute of Mental Health in Prague, which is currently a critical field. He is a good example of a new approach that is uncommon in the Czech Republic: combining disciplines previously thought to be incompatible, such as neuroscience with mental health or physics with philosophy.

What values do these students bring back from abroad?

I think one of the key values is courage—the courage to venture out into the world and face new competition. Many of our students were top performers at home, but abroad they are one of many; this teaches them humility and perseverance. The experience helps them develop a more realistic view of themselves and the world. They also build valuable connections and work alongside world-class experts, giving them tremendous insight. Their professors receive international awards, including Nobel Prizes. These are not teachers who started teaching 40 years ago and then stopped evolving.

And when will the Czech Republic itself be able to instill these values in its young people?

I already see significant progress, thanks to EU programs, the introduction of new disciplines, and opportunities for international students who come to study here. The Czech university scene is developing, offering courses in English and providing quality education that attracts students from other countries. I think this is an excellent step—combining the international experience of our students with the opportunity for foreigners to study and work here.

In September, Charles University made some changes regarding the recognition of diplomas from abroad. What impact will this have?

We signed a memorandum with Rector Králíčková to ensure that, where possible, students will be guided through the process with minimal time and financial burden. This is essentially the first step toward bringing more attention to the issue. Consider this: they graduate from the world’s top universities and want to work in the Czech public sector, for instance, but cannot do so until their diploma is officially recognized in the Czech Republic.

In theory, the process should take 30 days, but in practice, it can take up to six months. In some cases, diploma recognition may even be denied. This is a broader issue that needs to be addressed at the legislative level. We hope to make progress in resolving it.

The Bakala Foundation also runs courses for journalists from the Central European region. This is especially critical for countries like Hungary and Slovakia, which rank 67th and 29th, respectively, in the index of press freedom. Are you concerned that this regional discourse could spread to other countries?

I think it’s crucial for the value of media and journalistic work to be evaluated by experts and professionals, not politicians. Programs like Achilles Data teach journalists how to use investigative journalism methods and encourage them to tackle sensitive topics without fear. One of the program’s alumni was Ján Kuciak, which underscores the profound impact of this support.

This year, we succeeded in expanding the scope of Achilles Data to Ukraine. Despite the current situation, seven talented, young journalists from Ukraine attended the introductory training and will work under the guidance of outstanding investigative journalists from The Kyiv Independent.

This ties into the question of democracy and how it is approached. You are also a board member of the FW de Klerk Foundation, which focuses on defending and protecting South African democracy. Do you see populist and nationalist tendencies in Central Europe, the USA, and other parts of the world as a threat to modern democracy?

I do. Although we still live in a democratic world, the situation remains uncertain. For example, in the USA, President Trump’s refusal to acknowledge his defeat in the election against Biden undermined trust in institutions and the democratic system. That is a problem. South Africa, like the Czech Republic, went through a revolution around the same time, and their national hero was Nelson Mandela, who spent 26 years in prison. We had Václav Havel, and I am grateful to have witnessed the first meeting between Václav Havel and Frederik Willem de Klerk, and to have seen their perspectives on the world. While de Klerk was the last president under apartheid, he recognized the necessity of releasing Mandela from prison and handing over power without bloodshed. We managed a similar transition, and that is a tremendous success.

Is the situation in South Africa similar to Europe or the USA?

Although South Africa is now a large, democratic, wealthy country, it still faces issues such as migration, security, and unemployment. We tend to forget about it in Europe and the United States, which is a mistake. We should not stop paying attention to regions where we have invested or tried to transform autocratic regimes into free societies. The world will not function without international cooperation and openness. Today, wars are not only physical but also economic and, most importantly, informational.

This is why I am not comfortable with the nationalist approach seen in some countries today. These attitudes can have long-term negative consequences for our democracies. This mentality often leads to the identification of an external enemy to divert attention from domestic issues. This is dangerous, as examples from Russia, North Korea, and some Middle Eastern countries demonstrate. Conflicts often stem from internal problems and dissatisfaction within these nations.

How do you perceive the isolationism and protectionism of individual countries?

Quite negatively. The idea of fencing off a country will never work in the long term. Modern warfare includes economic and informational weapons, and if we lose trust in the exchange of information and collective security systems, we will be weaker.

This is why I dislike the growing nationalist and even fascist tendencies around the world. It’s a dangerous game that, in my view, cannot end well. When we look at the conflict between Ukraine and Russia, we must remain united in understanding who we are defending ourselves against and who our enemies are. Let’s not forget that today’s conflicts don’t begin with tanks crossing borders. Attempts to destabilize free countries, which are increasingly prevalent even in some EU states, undermine democracy. Concepts are distorted, misinformation and fear are spread. That’s where the conflict starts.

Who or what has an interest in spreading such an approach?

Anyone who would rather create conflict than build their own prosperity. Russia had a tremendous opportunity to educate and democratize its society, but it failed to capitalize on it. Instead, it uses the creation of external enemies to address its internal issues, whether economic or social. This is the oldest trick in the book, one that ultimately leads to tightening control.

Georgia, for instance, was Václav Havel’s last major topic, though he didn’t live to see it through. He was preparing to visit and give a lecture there. I remember how 15 years ago, we cried together over the fate of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, torn from Georgia and controlled by Russia.

In one of your interviews, you mentioned that preventing all of this is a fundamental task for education, which starts within the family. How do you raise your four children?

They are adolescents, and we try to approach each of them similarly, although the older ones claim the younger ones have advantages. Parenthood is a great opportunity for me because every day brings new challenges, and it’s always about adapting and learning. What’s important is how they will treat other people, their partners, and friends, and that begins to take shape in childhood.

How do you perceive the opportunities and privileges that today’s children have compared to your generation?

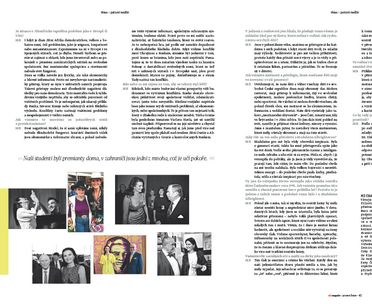

I am aware that our children—and all children in a free Czech Republic—have an immense gift. They can travel, access information, live in a free society, listen to the music they like, or play sports. Not everyone can afford everything, but if they want to, they can access experiences, information, and education. Our children grew up as “international citizens”—they are Czech, American, and have lived in Switzerland and South Africa. This has given them a broader view of the world and taught them to embrace different cultures, opinions, and beliefs. My husband and I are proud that, despite all the opportunities they have had, they remain humble and have a solid foundation to build upon.

How were you influenced by your friendship with Madeleine Albright?

Madeleine was always a great inspiration to me. She was a generation older than me, so she approached me more like a daughter. Beyond her natural charm and intelligence, she had the courage and strength to stand her ground. She wanted me to enter politics as well, but I always explained to her that I work where I feel I have an impact. Until the very end, she gently urged me. She was a great fighter with incredible energy—writing books, lecturing, teaching, and remaining an inspiration to all of us until the end.

You entered public life as the winner of the Miss Czechoslovakia pageant in 1991. How do you see the transformation of this competition and the position of women over the years? This is one of your topics, and it was also important to Madeleine Albright.

When it comes to beauty pageants, I think they should remain beauty competitions and not pretend to be something else. In the 1990s, when I participated, beauty was still relatively natural—there wasn’t as much plastic surgery, Botox, or other modifications that we often see in very young women and men today. I believe beauty can still be assessed today, but society and social media place enormous pressure on women. We see athletes, actresses, singers, and influencers half-naked on social media or in public, and this is not limited to celebrities. I think this harms women, especially teenage girls, far more than traditional beauty pageants.

How do you perceive the pressure that social media and the media exert on girls and women?

The pressure is enormous, and we all feel it. Every day, the media tells our eleven-year-old daughter how she should look. Her self-image is shaped by what is considered “in” or “out,” dictated by people who have no real authority on the matter. Natural beauty also has its advocates, but this voice is in the minority. A beauty pageant should be clearly defined, just as a singing competition is about the voice or sports are about performance. I see nothing wrong with women representing beauty and the female world view; it just needs to be fair and healthy.

Large European corporations will soon need to have at least a third of their leadership positions filled by women. What do you think about this?

I lean towards the idea that the position of women should grow naturally. On the other hand, we know that certain regulations can speed up this process and provide women with opportunities to establish their place in society during their professional lives. We see that in certain professions, like medicine, women already dominate. It’s important for the state to create an environment where women who have invested in their education can apply their skills and return to work without having to choose between family and career.

What else could help improve the position of women in the workplace?

I believe the key is to support women returning to work after maternity leave. When we invest in a young woman’s education, she should have the chance to use that investment. There’s also the issue of equal pay—there’s still a 17 percent pay gap between men and women in comparable positions. If society creates suitable conditions for women, they can fully utilize their potential, and this includes single mothers. I admire women who manage demanding careers while raising children—they deserve our support.